ABA therapy at InBloom Autism Services

The support you need from a team you can trust

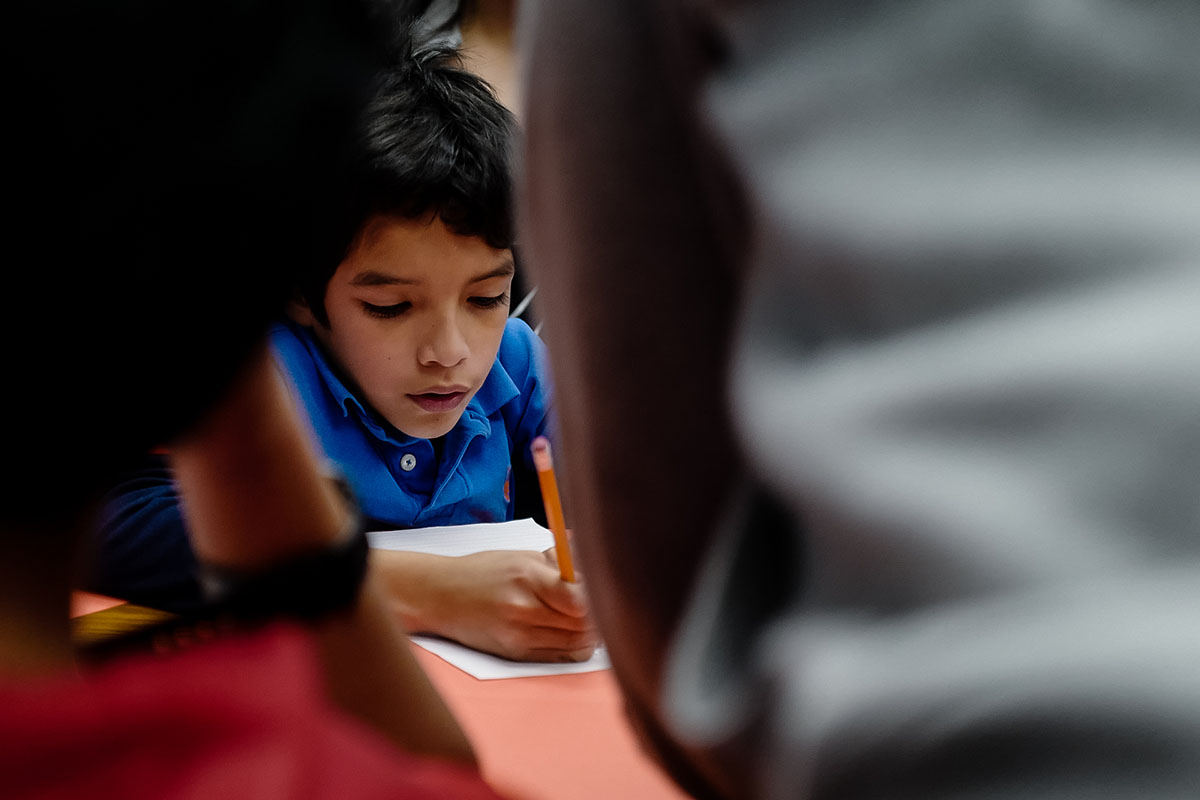

At InBloom Autism Services, we provide personalized ABA therapy for children with autism between the ages of 18 months and 5 years. Our programs are designed to build essential skills through play-based learning, helping each child gain confidence, communication, and independence.

From the initial evaluation to ongoing progress updates, our compassionate care teams guide families every step of the way, creating a supportive and transparent experience you can trust.

Ready to begin? Reach out to our team today at 888-754-0398.

Applied Behavior Analysis for Autism Explained

What Is ABA Therapy at InBloom?

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy is an evidence-based approach that helps children with autism develop communication, social, and daily living skills. Each treatment plan is individualized, using real-time behavioral data to track progress and shape meaningful outcomes.

At InBloom Autism Services, ABA therapy is delivered through naturalistic, play-based learning where every activity feels fun but is backed by clinical science. Sessions are filled with positive reinforcement and hands-on teaching moments that encourage participation, curiosity, and confidence.

Our goal is simple: to increase helpful behaviors and reduce those that interfere with learning, safety, and independence, empowering your child to thrive both in and outside the therapy center.

Developmental Skills We Work On

How can applied behavioral analysis therapy help?

ABA therapy helps children with autism develop the foundational skills needed for learning, communication, and independence. At InBloom Autism Services, all programs and services are customized to your child’s strengths and goals, blending structure with play-based learning to make every session engaging and rewarding.

Our clinicians use positive reinforcement and evidence-based techniques to teach new skills, encourage positive behavior, and help children reach important developmental milestones.

Expressive & receptive language

Communication is one of the most important skills developed in ABA therapy. Expressive language refers to how a child communicates, whether through words, gestures, picture exchanges, or communication devices. Receptive language focuses on how a child understands what others say, such as following directions or identifying objects.

At InBloom, therapists utilize fun and interactive methods to strengthen both areas. The goal is to help children express their needs clearly, understand others confidently, and build meaningful connections in daily life.

Behavior reduction

Behavior reduction is about understanding the why behind each behavior and helping children learn more effective ways to express themselves. Therapists use data-driven strategies to identify triggers and replace challenging behaviors with positive, functional communication.

Through consistent reinforcement and compassionate guidance, children learn to manage frustration, follow directions, and communicate their needs more effectively. The ultimate goal is to create lasting behavior change that supports confidence, cooperation, and success in everyday routines.

Functional communication

Functional communication teaches children how to express their needs in an appropriate and effective manner. Instead of using behaviors like crying or shouting, children with autism learn to ask for help, request a break, or seek attention using words, gestures, or communication tools.

By building these skills, therapy helps children reduce frustration, improve social understanding, and gain independence in communicating with others, both in the center and at home.

Academic readiness

Academic readiness focuses on preparing children with autism with the foundational skills they need to succeed in a classroom setting. Therapy sessions strengthen focus, listening, following instructions, and task completion through fun, play-based activities that feel like learning through play.

By developing these early academic behaviors, children build confidence, motivation, and persistence, helping them transition smoothly into structured school environments and everyday learning situations.

Social and group skills

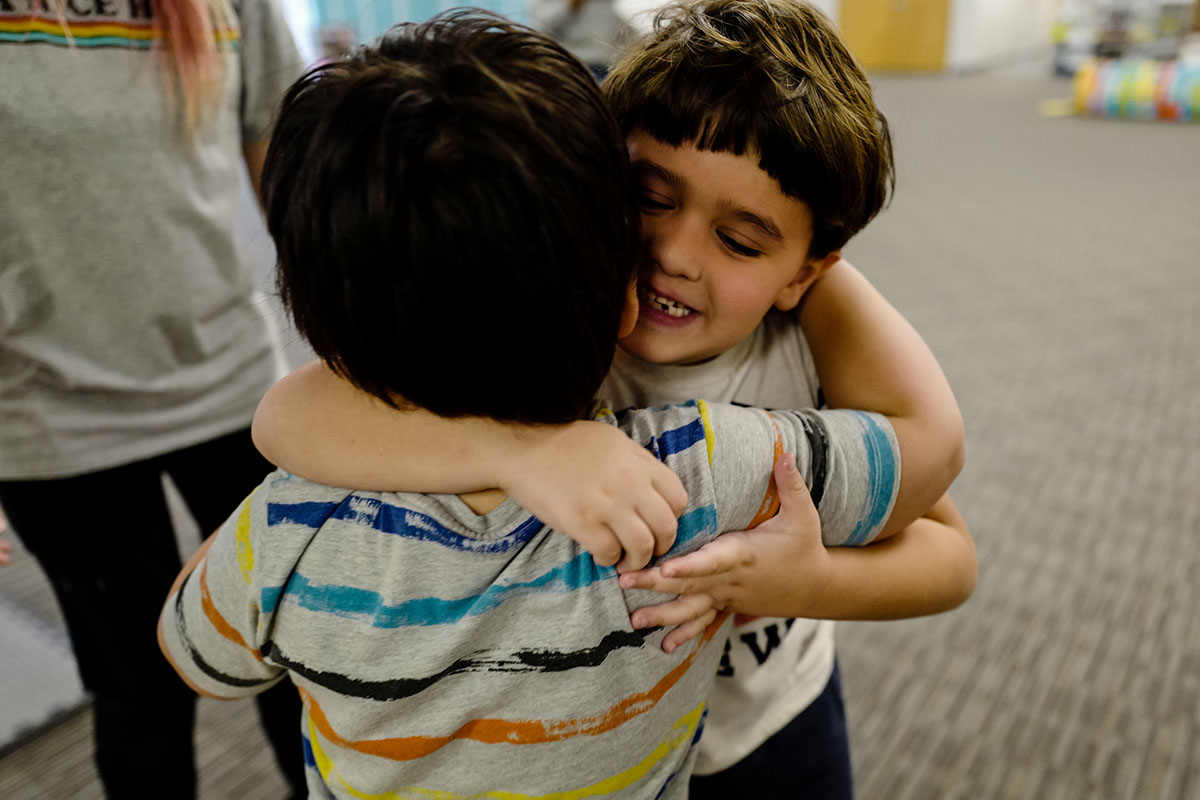

Social and group skill development helps children learn how to connect, share, and play with others in meaningful ways. Through structured activities and guided peer interaction, children practice turn-taking, problem-solving, initiating conversations, and cooperative play.

These experiences build confidence, empathy, and teamwork, helping children form friendships and apply social skills naturally in everyday situations.

Toilet training & daily living skills

Toilet training and daily living skills are key steps toward independence. Our therapists use structured routines, visual supports, and encouragement to help children learn skills like using the bathroom, handwashing, getting dressed, and brushing teeth.

Each success is celebrated, reinforcing confidence and helping children build habits that promote independence at home, school, and in the community.

Caregiver training

Caregiver training empowers families to become active partners in their child’s progress. Through direct coaching with a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA), parents learn the same strategies used in therapy to encourage growth at home.

This collaboration builds confidence, strengthens family connections, and ensures consistency across every environment where learning and progress happen.

Goals and outcomes of ABA therapy

ABA therapy helps children with autism build real-world skills that lead to lasting growth. Each program is designed to teach through positive reinforcement, consistency, and play, so progress feels natural, achievable, and fun. Families can expect to see meaningful improvements in communication, independence, and daily routines over time.

Building foundational skills through ABA therapy

ABA therapy helps strengthen early developmental skills like communication, attention, and social connection. These are the building blocks for learning and success at home, in school, and in the community. In a large health-system study, 58% of children in ABA achieved meaningful gains by 12 months and 54% by 24 months, with the greatest progress observed in children who initially had the most support needs.

Encouraging independence and daily life successes

ABA therapy promotes independence by helping children master everyday routines, such as getting dressed, following directions, and completing simple tasks. These achievements may seem small, but they add up to big moments of pride and self-confidence that carry into every part of life and continued learning.

Is ABA autism therapy right for my child?

Between the ages of 1 and 5, children experience some of the most rapid brain development of their lives. That’s why early intervention through ABA therapy can make a profoundly meaningful difference, helping children acquire essential skills for communication, learning, and independence.

At InBloom Autism Services, our Care Team walks families through every step of the process, from your first call to your child’s first day in therapy. We want parents and caregivers to feel confident, informed, and supported by a team that genuinely cares about their child’s success.

In this episode of Blooming Minds, one of our Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs) explains what to expect when starting ABA therapy services with InBloom.

How do I know if we qualify for autism services or therapy?

Getting started with ABA therapy begins with a few simple questions to help us determine the right path for your child. During your first call, our Care Team will guide you through an easy screening process and verify your insurance coverage so you know exactly what to expect.

You may qualify for ABA therapy at InBloom if:

- Your child is between 18 months and 5 years old

- Your child has a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or is in the process of being evaluated

- You’re looking for center-based ABA therapy designed to build communication, social, and daily living skills

If you’re unsure where to begin, we’ll walk you through each step, from confirming coverage to matching your family with a local care team.

guiding families every step of the way

Types of ABA Therapy & ABA Techniques

What can I expect from ABA treatment?

ABA therapy is a journey built on patience, consistency, and teamwork. Progress happens one step at a time, and every session helps your child grow in communication, confidence, and independence.

After assessing your child’s unique strengths and needs, our clinicians create a personalized treatment plan, typically ranging from 20 to 40 hours of center-based therapy per week. Throughout this process, your child’s circle of support expands to include dedicated therapists, a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA), and, most importantly, you.

We believe the most meaningful progress happens when caregivers and clinicians work together. By staying connected with your child’s ABA team, you’ll help reinforce new skills at home and celebrate every milestone along the way.

support From today to the start of care

What does getting started in ABA autism therapy and services look like?

Connect with our Care Team by phone or by filling out our contact form.

During our first call, we’ll ask about your child’s age, any challenging behaviors, and verifying if your family has received an official diagnosis for ASD.

Send us your insurance information & diagnostic evaluation support, and we’ll confirm that ABA therapy is covered by your insurance plan.

Your local InBloom team will send an introductory email and work with you to schedule an assessment.

Within a week of assessing your child’s skills and behaviors, the BCBA (Board Certified Behavior Analyst aka the senior clinician on your child’s care team) will review the prescribed treatment plan with you.

Once you have signed the treatment plan, our team will submit it to your insurance. It can take several weeks, but once the plan has been approved, your local team will reach out to schedule the start of your kiddo’s care!

Don’t have a diagnosis? We offer autism diagnostic evaluations!

*Diagnostic services coming to Connecticut in February 2026!

If your child is showing signs of autism but hasn’t received a formal diagnosis yet, InBloom can help. We’re proud to offer gold-standard, comprehensive autism diagnostic evaluations (ADOS-2 or Tele-ASD-Peds) for children between 18 months and 3 years old.

Our evaluations are performed by experienced clinicians who take the time to understand your child’s unique strengths and challenges. From the first conversation to the results review, our goal is to guide your family with clarity and compassion so you can take the next step toward the right support and care.

Call 888-754-0398 to find out if you qualify for an autism diagnostic evaluation in Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Texas, or Wisconsin.

Take the next step in your unique autism therapy journey

Every child’s path is different, and we’re here to support yours. Whether you’re just starting to explore ABA therapy or ready to begin services, our Care Team will walk you through each step, from your first call to your child’s first day in therapy.

If you’re ready to learn more or schedule your initial consultation, we’re just a call or click away.

Can’t chat today? Fill out our contact form here!

Testimonials

Get Focused Teamwork.

Caregivers are an essential part of our team.

Frequently asked questions about ABA therapy

Parents often have questions about how ABA therapy works, what to expect, and how it can support their child’s development. Below are answers to some of the most common questions we receive at InBloom Autism Services.